Welcome to our guide to German adjective declension. In this post, we will introduce you to the rules of adjective declension in German, covering how and when you need to change the ending of a German adjective. This will always depend on the word’s gender, number (singular or plural), and its case.

Throughout this post, we'll provide you with examples of adjective declensions and we will identify the rules required for each ending. This may sound a bit difficult at first, but don’t worry – we've got you covered!

Soon, you will understand the essential rules required to master German adjective endings. And if you still want to deepen your German language skills with diverse resources, why not practice watching German TV shows with Lingopie?

Lingopie is an online streaming platform that teaches you German through TV shows and movies. Get started with a 7-day free trial today!

What is a German Adjective Ending & Why do German Adjective Endings differ?

We all know that the German language is complex. This is due to its different 'cases' and the number of irregular verbs in the German language. There are many many linguistic challenges that you will need to overcome if you want to learn German grammar properly.

German sentences often require different declensions. This refers to the way that articles, adjectives and sometimes nouns can change their form to reflect their role in the sentence.

Throughout this article, we will show you how different declensions of adjectives give indications about a sentence's subject, object, etc. Remember, in German, different endings are grammatically necessary.

Two Types of German Adjectives

When learning German adjective endings, you need to know that there are two types of adjectives: One type is predicative adjectives; these adjectives come after the noun:

- The sky is blue (Der Himmel ist blau)

- The house is big (Das Haus ist groß)

These types of adjectives do not require a declension.

The other type of adjectives are attributive adjectives; these come before a noun and they are declined according to it:

- The blue sky is without clouds (Der blaue Himmel wolkenlos)

- The big house looks great (Das große Haus sieht toll aus)

Remember that the difference in declension comes from the position of the adjective. This is the first basic rule to remember for German adjective endings.

As we mentioned earlier, German adjective endings depend on the following elements of a sentence: the adjective's gender, number (singular or plural), and its case.

Let's look at essential German grammar to understand the affecting factors of word endings.

The German Articles

Let's look at some essential rules in German grammar, starting with a basic linguistic element: The articles.

In German, there are definite (bestimmte) articles and indefinite (unbestimmte) articles.

While the English definite article is ‘the’, and the indefinite article ‘a /an’, German articles have genders (masculine, feminine, neutral), which work as follows:

Der Hund (m; dog)

Die Sonne (f; sun)

Das Haus (n; house) are the three definite articles for nouns in singular.

Ein (m/n) and eine (f) are the indefinite articles.

Depending on who the subject or object in a sentence is, the article’s conjugation differs.

Sometimes, there are indications that may help you guess the gender: If a word ends in ‘e’, it’s likely to be feminine: die Sonne (sun).

See below an exemplary group of nouns and their gender, starting with the singular masculine noun:

- Nouns for the seasons: Der Frühling (spring), Der Sommer (summer), Der Herbst (autumn) Der Winter (winter). A fun fact, however, is that the word ‘season’ (‘Jahreszeit’) is feminine.

Feminine nouns can be grouped based on suffixes:

- Words ending in ‘-ung’ or ’keit’: Die Heizung (radiator); Die Möglichkeit (possibility).

The plural article is Die. Regular examples for masculine, neutral and feminine plural nouns:

- Die Hunde (m; dogs) = -e ending

- Die Worte (n; words) = -e ending

- Die Maschinen (f; machines), Die Mauern (f; walls) = -n ending

But why look at the gender of articles and their rules? And how is this relevant to adjective endings?

Well, it's quite simple: The correct ending of an adjective also depends on the gender of a noun. Hence, we need to take basic German article rules into account.

Let's now move to German cases.

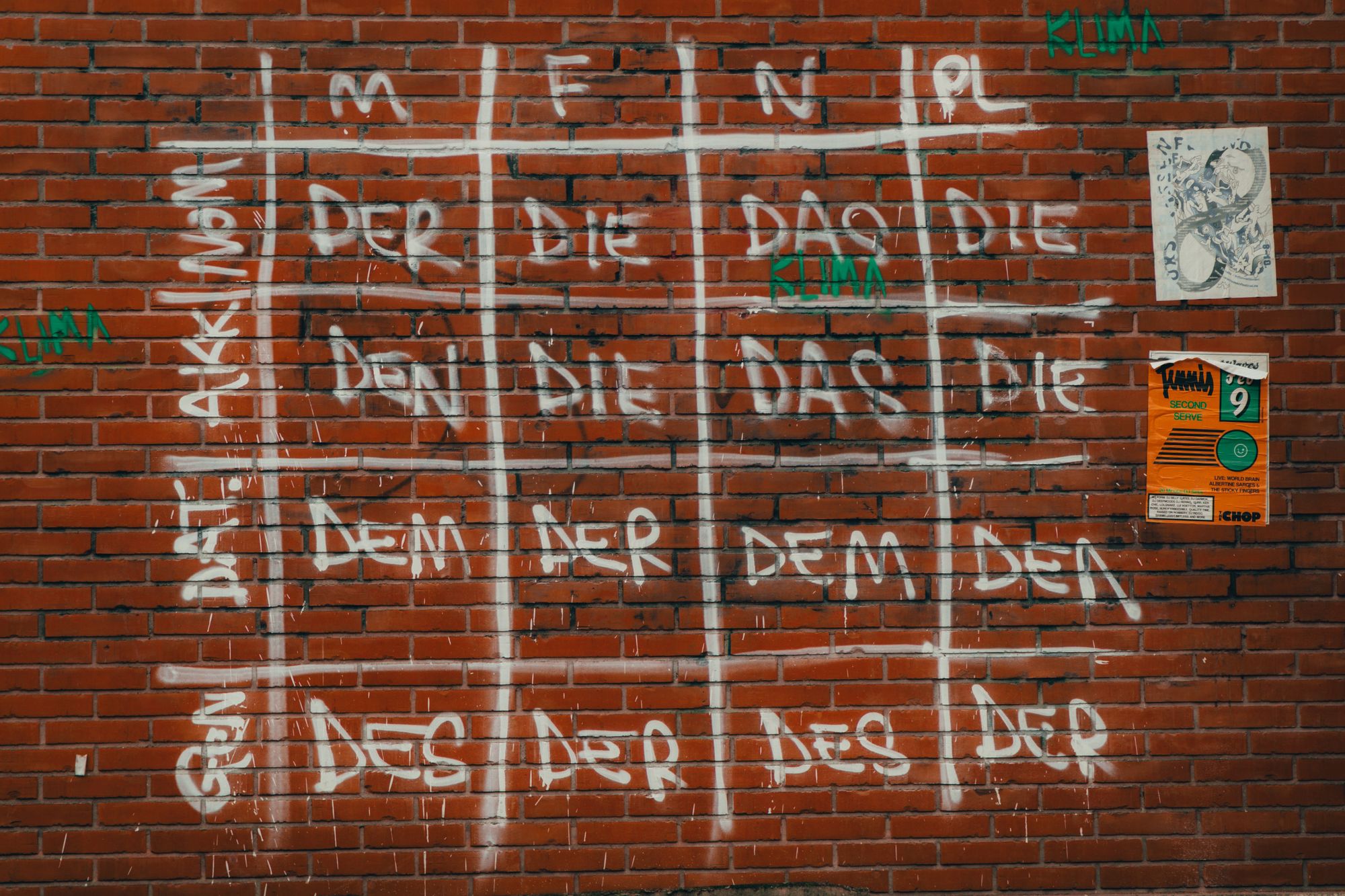

The German Case System

As you might have heard, there are four different cases in German grammar.

These are the nominative (subject), accusative (direct object), dative (indirect object), and genitive (possessive) cases.

These four German cases play major roles. We are sure you have heard about nominative and accusative cases when studying intermediate German grammar, and it is important to understand the nature of the four German cases properly.

Here is an overview of the different cases and their according articles:

Note: German words change their form into various endings, according to their function in a sentence. This could be in a sentence with elements to define relationships, including possessive pronouns (mine, ours, hers, his, theirs...), or sentences with subject and verb only.

Very briefly speaking, you need to know that:

- the nominative case is describing the subject of a sentence

- The accusative case is for direct objects

- The dative case is for indirect objects

- The genitive case is used to express possession.

Let's not get into too much detail here such as feminine nominative or masculine nominative... If you need to refresh your knowledge of German cases, have a look at this article.

Three Types of German adjective declensions

Now that was 'ein bisschen' German basics – let's get back to the part about the adjectives.

We will now look at the different types of German adjectives and their declension patterns.

As this goes back to a noun's case, we also look at the word that introduces the adjective.

The three types of declension patterns are as follows:

- A Weak declension is if the adjective follows a definite article (der/die/das).

= The sentence structure is: definite article + adjective + noun - A Strong declension is if the adjective does not follow an article.

= The sentence structure is: no article + adjective + noun - Mixed declension is used after the indefinite article (ein/eine/ein).

= The sentence structure is: indefinite article (ein, eine …)/ possessive (mein...) / negation article (kein) + adjective + noun

Weak Declensions

Let's start with the first type. Weak declension pattern is used in sentences like these ones:

- Das ist die beste Note, die ich je hatte (This is the best grade I have ever had)

- Es ist der schönste Tag meines Lebens (It is the nicest day of my life)

Looking at weak endings, you need to learn these endings for weak declensions in German:

Nominative case:

-e; -e; -e; -en (masculine; feminine; neutral; plural)

Accusative case:

-en; -e; -e; -en (masculine; feminine; neutral; plural)

Dative case:

-en; -en; -en; -en (masculine; feminine; neutral; plural)

Genitive case:

-en; -en; -en; -en (masculine; feminine; neutral; plural)

In these examples of weak endings, you can tell that dative and genitive endings are consistent: Their plural forms all end in -en.

You also see that other forms are clear to identify and that weak declension can be regarded as the easiest form of German adjective declension.

Strong Declensions

A strong declension is used in sentences without articles – such as in these two sentences:

- In Frankreich gibt es leckere Croissants (In France, there are delicious croissants)

- In Supermärkten findest du frisches Obst (In supermarkets, you find fresh fruit)

Nominative case:

-er; -e; -es; -e (masculine; feminine; neutral; plural)

Accusative case:

-en; -e; -es; -e (masculine; feminine; neutral; plural)

Dative case:

-em; -er; -em; -en (masculine; feminine; neutral; plural)

Genitive case:

-en; -er; -en; -er (masculine; feminine; neutral; plural)

In these examples, you can tell that strong endings often occur when a sentence focuses on defining where something is (In Frankreich; In Supermärkten) and no article is used/ required.

Mixed Declensions

You will use a mixed declension in these cases:

- Du hast ein schönes Haus (You have a beautiful house)

- Sie haben einen schönen Garten (They have a beautiful garden).

Nominative case:

-er; -e; -es; -en (masculine; feminine; neutral; plural)

Accusative case:

-en; -e; -es; -en (masculine; feminine; neutral; plural)

Dative case:

-en; -en; -en; -en (masculine; feminine; neutral; plural)

Genitive case:

-en; -en; -en; -en (masculine; feminine; neutral; plural)

One thing to remember here is that we also use if for adjectives following the word 'kein' (no):

- Es ist kein schöner Tag (It is not a nice day).

All these different examples of declension show that it is very hard to define the same type of ending easily.

However, there are rules you can look at to see which ending an adjective takes.

If you understand the noun + article and the case a sentence is in, the adjective ending follows.

Summing up: A Guide to German Adjective Declension

Hopefully, you can now identify declension patterns as you have gained an overview of the different types of declension, including a weak declension, a mixed declension, or a strong declension.

In this article, we have covered the nature of German adjective endings in relation to other elements such as nouns, (their) genders, and cases.

Remember: An adjective ending in German does not necessarily need to change – attributive adjectives do not require an adapted adjective ending.

Try to become familiar with the three main types of declension and do not get lost in the complexity of the German language – it all comes with time!

If you want to do something fun associated with German, why not check out Lingopie and start watching German TV shows and movies? This provides a great new way to interact with the German language.

Related: The Best Way to Learn German as a Beginner

Access your free 7-day-trial today!

![A Guide to Adjective Declension in German [Grammar]](http://lingopie.com/blog/content/images/size/w1200/2022/10/declination-german.webp)

![The 9 Best Jobs for Polyglots Today [Career Advice]](http://lingopie.com/blog/content/images/size/w1200/2022/10/The-9-Best-Jobs-for-Polyglots-Today.webp)

![Top 25 German Movies And Series To Learn German Fast [For Beginners]](http://lingopie.com/blog/content/images/size/w300/2024/05/Top-German-Movies-and-Series-to-Learn-German-Fast--For-Beginners-.jpg)